Peer Reviewed

Trichobezoars

AUTHORS:

Poonam Mahajan, MD

Hurley Medical Center/Michigan State University, Flint

LaDonna Johnson, MD

Children’s Hospital of Michigan, Detroit

CITATION:

Mahajan P, Johnson L. Trichobezoars. Consultant for Pediatricians. 2012;11(5):148-149.

For the second time in a week, a 6-year-old girl was brought to the hospital with poorly localized epigastric and periumbilical pain. The pain was crampy and when severe, the child would yell. There was no aggravating or relieving factor. She also had 8 to 10 episodes of nonbilious, nonbloody vomiting. At the previous hospital visit, the patient had similar complaints of vomiting and abdominal pain and was treated for constipation.

The child had no history of abdominal distension, loose bowel movements, blood in stool, jaundice, fever, or urinary complaints. The mother was concerned about the child’s weight because her twin sister weighed 15 lb more. The patient was a picky eater. She was doing well in school and at home but was described as moody and stubborn. The mother vaguely mentioned that 2 years earlier the child ate paper and at times wound her hair around her tongue.

On admission, vital signs and physical examination findings were unremarkable, specifically there was no alopecia. Results of laboratory tests, including a complete blood cell count, electrolyte levels, liver function, and urinalysis, were normal.

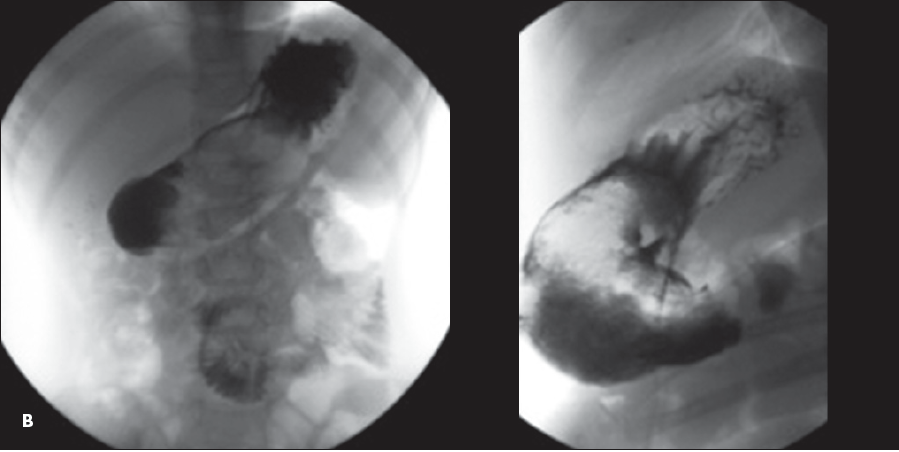

A plain abdominal radiograph revealed a mottled density over the gastric body and antrum (A). Findings on ultrasound examination suggested a few scattered lymph nodes in the periumbilical area and right lower quadrant. An upper GI barium study showed filling defects in the gastric body and proximal jejunum, which were highly suggestive of a trichobezoar, considering the history (B). During exploratory laparotomy with gastrotomy and jejunotomy, 3 trichobezoars were removed (C).

The term “bezoar” is thought to be derived from the Arabic term “badzeh” or the Persian term “panzeh,” which means antidote or counter-poison.1,2 A bezoar is an accumulation of exogenous material in the stomach or intestine. Bezoars have also been found in the esophagus and rectum.3 The accumulated material can be food (phytobezoar), milk (lactobezoar), hair (trichobezoar), or medicine (pharmacobezoar). Rare causes include chewing gum, gummy bears, sunflower seeds, pumpkin seeds, and plaster casts. Bezoars occur more commonly in patients who have had certain procedures, such as bariatric surgery or gastric banding, and in patients with psychiatric conditions.

Trichobezoar, caused by the ingestion of hair, occurs mostly in girls and young women, with a peak incidence in the second decade of life.4 Trichobezoars can become large and cause signs and symptoms of partial or complete intestinal obstruction, intestinal perforation (Rapunzel syndrome), and abdominal wall abscess.5 Malabsorption is another potential complication of a large bezoar.4 The presence of simultaneous trichobezoars at 2 different sites in the GI tract is also possible.6

Diagnosis of bezoars requires a high index of suspicion because the presentation is often vague and misleading. The mass can be suggested on plain radiographs, barium studies, and CT scans. The characteristic finding on an abdominal CT scan is a nonhomogeneous, nonenhancing mass in the lumen of the stomach or small bowel.4 Tiny air pockets within the mass may give it a mottled appearance, simulating small bowel obstruction.7 Oral contrast circumscribes the mass and may fill the interstices near the surface.

Bezoars can be removed endoscopically. Large bezoars may need surgical intervention.4 For all patients with bezoars, assessment and follow-up by a psychologist is important.

REFERENCES:

- Lynch KA, Feola PG, Guenther E. Gastric trichobezoar: an important cause of abdominal pain presenting to the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2003;19(5):343-347.

- Williams RS. The fascinating history of bezoars. Med J Aust. 1986;145(11-12):613-614.

- Goel AK, Seenu V, Srikrishna NV, et al. Esophageal bezoar: a rare but distinct clinical entity. Trop Gastroenterol. 1995;16(1):43-47.

- Kelson J, Liacouras C. Bezoars. In: Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB, et al. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 19th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier;2011:1291.

- Zaharie F, Iancu C, Tant¸a˘u M, et al. Laparoscopic treatment of a large trichobezoar in the stomach with gastric perforation and abdominal wall abscess [in Romanian]. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2010;105(5):713-716.

- Hoover K, Piotrowski J, St Pierre K, et al. Simultaneous gastric and small intestinal trichobezoars--a hairy problem. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41(8):1495-1497.

- Morris B, Shah ZK, Shah P. An intragastric trichobezoar: computerised tomographic appearance. J Postgrad Med. 2000;46(2):94-95.

1. Lynch KA, Feola PG, Guenther E. Gastric trichobezoar: an important cause of abdominal pain presenting to the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2003;19(5):343-347.

2. Williams RS. The fascinating history of bezoars. Med J Aust. 1986;145(11-12):613-614.

3. Goel AK, Seenu V, Srikrishna NV, et al. Esophageal bezoar: a rare but distinct clinical entity. Trop Gastroenterol. 1995;16(1):43-47.

4. Kelson J, Liacouras C. Bezoars. In: Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB, et al. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 19th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2011:1291.

5. Zaharie F, Iancu C, Tant¸a˘u M, et al. Laparoscopic treatment of a large trichobezoar in the stomach with gastric perforation and abdominal wall abscess [in Romanian]. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2010;105(5):713-716.

6. Hoover K, Piotrowski J, St Pierre K, et al. Simultaneous gastric and small intestinal trichobezoars--a hairy problem. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41(8):1495-1497.

7. Morris B, Shah ZK, Shah P. An intragastric trichobezoar: computerised tomographic appearance. J Postgrad Med. 2000;46(2):94-95.