DISCUSSION:

DISCUSSION:The child has orbital cellulitis, an infection with sometimes serious sequelae that involves the soft tissue of the orbit posterior to the orbital septum. Children are more likely than adults to contract orbital cellulitis; the median age of those affected is 7 years. Preseptal cellulitis--the other major infection of the ocular and adnexal orbital tissue--involves the soft tissue of the eyelids and periocular region anterior to the orbital septum and is considered less severe.

Etiology and pathogenesis. Orbital cellulitis has a variety of causes:

•Direct extension of infection from the periorbital structures--usually the paranasal sinuses, but also the face, globe, eyelids, ocular adnexum or other periocular tissue, or lacrimal sac.

•Direct inoculation of the orbit from trauma or surgery.

•Hematogenous spread from bacteremia.

Venous drainage from the middle third of the face, including the paranasal sinuses, occurs mainly via the orbital veins. Because these veins do not have valves, they allow antegrade and retrograde passage of infection. Osteomyelitis of the orbital bones, phlebitis of the facial veins, and dental infection may also result in orbital cellulitis.

Ethmoidal sinusitis accounts for more than 90% of all cases of orbital cellulitis. Edema of the sinus mucosa with subsequent blockage of normal sinus drainage allows indigenous microflora to proliferate and invade the edematous mucosa, which results in suppuration. The organisms, usually aerobic non-spore-forming bacteria, gain access to the orbit through the thin bones of the orbital walls, venous channels, foramina, and dehiscences. Subperiorbital and intraorbital abscesses may occur.

Any injury involving perforation of the orbital septum may secondarily result in orbital cellulitis. Orbital inflammation may occur as soon as 48 to 72 hours after an injury. In the case of a retained orbital foreign body, the onset of inflammation may be delayed for months.

Orbital cellulitis occurs more frequently during the winter because of the increased incidence of sinusitis. Before the advent of antibiotics, the mortality associated with orbital cellulitis was 17%; 20% of survivors became blind in the affected eye. Prompt diagnosis and appropriate antimicrobial therapy have significantly reduced these rates.

Diagnosis. Cardinal signs and symptoms include proptosis, ophthalmoplegia, and chemosis, which result from elevated intraorbital pressure and which may be associated with orbital pain and tenderness, purulent nasal discharge, conjunctival hyperemia, and resistance to retropulsion of the globe. Other findings include limited ocular motility, pain with eye movement, reduced visual acuity, orbital congestion, headache, fever, lid edema, rhinorrhea, and malaise.

Suspect orbital cellulitis in any child who presents with facial or dental infection in association with any of the above findings.

Leukocytosis with a left shift is common. It is best to obtain blood cultures before administering antibiotics, although cultures infrequently reveal the responsible organism. Send samples of purulent nasal material for cultures and Gram staining.

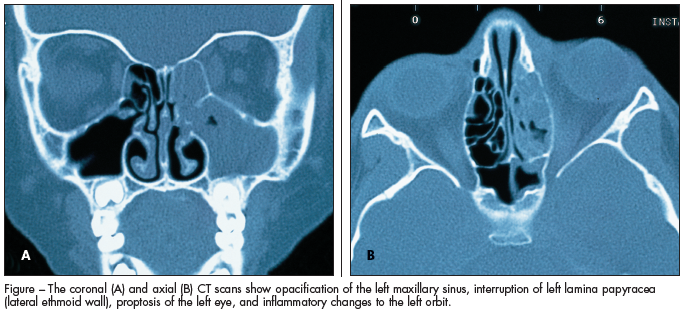

High-resolution CT scans, including axial and coronal views (Figure), are imperative. MRI may help de-fine orbital abscesses and evaluate the possibility of cavernous disease. Consultation with specialists in infectious disease, ophthalmology, or otolaryngology is recommended.

Treatment. Prompt hospitalization and administration of intravenous antibiotic therapy are imperative for successful treatment. Therapy for orbital cellulitis associated with ethmoidal sinusitis should include coverage for Streptococcus pneumoniae and other streptococci, Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, and non-spore-forming anaerobes.

Dental infections that result in maxillary and orbital cellulitis are typically attributable to microorganisms indigenous to the mouth, including anaerobes. The usual culprits are Bacteroides species. Soft tissue infections of the eyelids and face are most commonly caused by staphylococci and Streptococcus pyogenes. Administer an antifungal if Mucor and Aspergillus species are found to be the culprit organisms. Tetanus prophylaxis should be updated as needed.

The infection in the present case was thought to have resulted from maxillary sinusitis. The patient was admitted to the hospital, where she was treated with intravenous ampicillin and sulbactam( sodium. The erythema decreased significantly after 1 day and the swelling after 3 days. On discharge, the patient underwent an 18-day course of treatment with amoxicillin( and potassium clavulanate and recovered completely.

Case and images courtesy of David Effron, MD, Case Western Reserve University.