Man With a Diffuse Palpable Rash

A 46-year-old man with a history of asthma and hyperlipidemia presents with migrating polyarthralgia, swelling of the extremities, and a worsening purpuric, raised rash of 1 week’s duration.

A 46-year-old man with a history of asthma and hyperlipidemia presents with migrating polyarthralgia, swelling of the extremities, and a worsening purpuric, raised rash of 1 week’s duration.

HISTORY

He reports that about 2 weeks earlier his right knee became painful, swollen, and warm to the touch; his left knee became painful and warm 1 day later. He also had several raised red spots on the posterior aspect of his left calf that were itchy but not painful. The next day the rash progressed to his left knee, and he began to experience severe epigastric pain along with shortness of breath and lightheadedness. Later the rash progressed to involve his feet, arms, and trunk with bilateral swelling of the ankles and hands as well as worsening pain in his feet such that he was unable to stand or walk.

The patient has a recent history of postprandial diarrhea that resolved 4 days earlier. He describes the diarrhea as watery, brown, and associated with occasional passage of blood. He denies fever, headache, dizziness, chest pain, dysuria, and change in the color of his urine.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Temperature is 36.7°C (98.1°F); heart rate, 68 beats per minute; blood pressure, 112/73 mm Hg; and respiration rate, 16 breaths per minute. There is a diffuse palpable rash on both lower extremities that extends to the trunk and involves the groin and buttocks. An extensive bilateral rash is also noted on the elbow extensor surfaces with some lesions on the hands and forearms. No lesions are evident on the neck or face. Palpation of the medial aspect of the right knee and both ankles elicits tenderness; bilateral non-pitting edema of the ankles is noted.

A stool guaiac test is negative.

WHAT’S YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

Figure 1 - Palpable purpura is visible on the patient's buttocks and trunk.

This patient has Henoch-Schonlein purpura (HSP), a vasculitis with IgA-dominant immune deposits that affects small vessels, including capillaries, venules, and arterioles. HSP presents with cutaneous involvement in 90% of patients in the form of palpable purpura, especially on the buttocks and legs (Figure 1); 75% have musculoskeletal involvement, which includes arthralgia and arthritis; and 60% experience GI symptoms, including colicky abdominal pain and melena. The clinical presentation of HSP is more severe in adults than in children, and the renal prognosis for HSP-related nephritis is also worse in adults than in children.

HSP is primarily a childhood disease that occurs between the ages of 3 and 15 years; it is much less common in adults. There is a male predominance with reported male-to-female ratios of 1.2:1 to 1.8:1. HSP is seen less frequently in black children than in white or Asian children.

DIAGNOSIS

In 1990 the American College of Rheumatology established criteria for the diagnosis of HSP. The patient must meet at least 2 or more of the following 4 criteria:

•Palpable purpura.

•Age less than or equal to 20.

•Bowel angina.

•Wall granulocytes on biopsy.

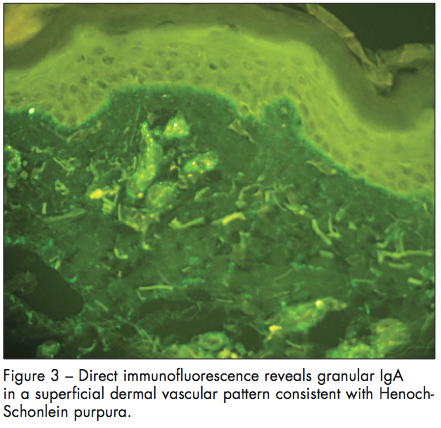

The presence of 2 or more criteria leads to a sensitivity of 87.1% and a specificity of 87.7%. Immunofluorescence studies show IgA, C3, and fibrin deposition within the walls of involved vessels.

TREATMENT

The treatment regimen depends on the severity of the presentation and the appearance of the biopsy sample. Choices include oral corticosteroids or a combination of intravenous methylprednisolone, cyclophosphamide, and dipyridamole followed by prednisone. For severe cases that do not respond to these treatments, intravenous immunoglobulin can be used. Analgesics may be used for patients who have abdominal and joint pain.

OUTCOME OF THIS CASE

The patient was admitted. Oral prednisone was initially started but was subsequently switched to intravenous prednisolone after nausea and vomiting developed without improvement in the rash. High-dose proton pump inhibitor therapy was also started for the abdominal pain. A skin biopsy was obtained, which showed perivascular neutrophils, leukocytoclasis, extravasation of erythrocytes, and fibrin associated with blood vessels (Figure 2); immunofluorescence revealed granular IgA in a superficial dermal vascular pattern consistent with HSP (Figure 3). The patient’s rash improved during his hospital stay, and he was discharged on day 4 with a 9-week tapering regimen of oral prednisone.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Hypersensitivity vasculitis (HSV). The American College of Rheumatology defines HSV when 3 of the following 5 criteria are met:

•Age older than 16.

•Use of a possible offending drug in temporal relation to the symptoms.

•Palpable purpura.

•Maculopapular rash.

•Biopsy of a skin lesion showing neutrophils around an arteriole or venule.

The only differentiation from HSP is that HSP is characterized by the deposition of IgA in the skin lesion. The treatment is discontinuation of the inciting drug or cure of the underlying infection; in severe cases not caused by infection or drugs, colchicine, antihistamines, and dapsone can be used.

Meningococcemia. The typical presentation of meningitis due to Neisseria meningitidis consists of the sudden onset of fever, nausea, vomiting, headache, diffuse rash, decreased ability to concentrate, and myalgia in a young healthy patient. The rash ranges from petechial to hemorrhagic in appearance, and the maculopapular rash is classically found on the trunk and lower extremities. On physical examination, meningeal irritation can be induced via Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s signs, but its absence does not exclude the diagnosis. Blood cultures and lumbar puncture can be performed but should not delay treatment. The treatment consists of early antibiotic therapy with a third-generation cephalosporin or chloramphenicol.

Mixed cryoglobulinemia. The major clinical manifestations of mixed cryoglobulinemia include palpable purpura, arthralgia, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, peripheral neuropathy, and hypocomplementemia (especially low C4 levels). They occur in patients with chronic liver disease, especially hepatitis C, and also in patients with HIV infection. The manifestations result from deposition of antigen-antibody complexes in small and medium-sized arteries. The diagnosis is made on the basis of the history, palpable purpura, low complement levels, and detection of circulating cryoglobulins in the patient’s blood. Among the therapeutic options are plasmapheresis, treatment of underlying hepatitis C virus infection, interferon alfa, or rituximab.

Acknowledgment: The authors thank Keira L. Barr, MD, FAAD, FASDP, assistant professor of clinical dermatology and pathology at UC Davis, for Figure 2 and the pathology interpretation.

FOR MORE INFORMATION:

- Chen KR, Carlson JA. Clinical approach to cutaneous vasculitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9(2):71-92.

- Jennette CJ, Falk RJ. Small-vessel vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1512-1523.

- Kinney MA, Jorizzo JL. Small-vessel vasculitis. Dermatologic Therapy. 2012;25:148-157.

- Kraft DM, McKee D, Scott C. Henoch-Schonlein pupura: a review. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58(2):405-408.

- Mills JA, Michel BA, Bloch DA, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Henoch-Schonlein Purpura. Arthritis Rheum. 990;33:1114-1121.

- Pillebout E, Thervet E, Hill G, et al. Henoch-Schonlein purpura in adults: outcome and prognostic factors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1271-1278.