Hungry Bone Syndrome Precipitating Ventricular Tachycardia

Authors:

Stacie N. Hamley, MD; Nisha Surenderanath, MD; and Melissa A. Carlucci, MD

University of Tennessee College of Medicine, Chattanooga, Tennessee, and Children’s Hospital at Erlanger, Chattanooga, Tennessee

Citation:

Hamley SN, Surenderanath N, Carlucci MA. Hungry bone syndrome precipitating ventricular tachycardia [published online January 18, 2018]. Consultant360.

A 15-year-old girl with a history of primary hyperparathyroidism underwent partial parathyroidectomy with removal of an encapsulated parathyroid adenoma. She had an uneventful postoperative course and was discharged on postoperative day 1 on oral supplements of calcium and calcitriol.

On postoperative day 4, she presented with bilateral lower extremity weakness and paresthesia. She had a positive Chvostek sign, and her lower extremity muscle strength was mildly diminished.

Laboratory test results at the time of admission showed a serum calcium level of 6.9 mg/dL (reference range, 8.9-10.8 mg/dL), a phosphorous level of 2.7 mg/dL (reference range, 2.8-5.2 mg/dL), and a magnesium level of 1.4 mg/dL (reference range, 1.7-2.2 mg/dL). She received 2 doses of intravenous (IV) calcium gluconate and was started oral calcium carbonate, magnesium oxide, and calcitriol.

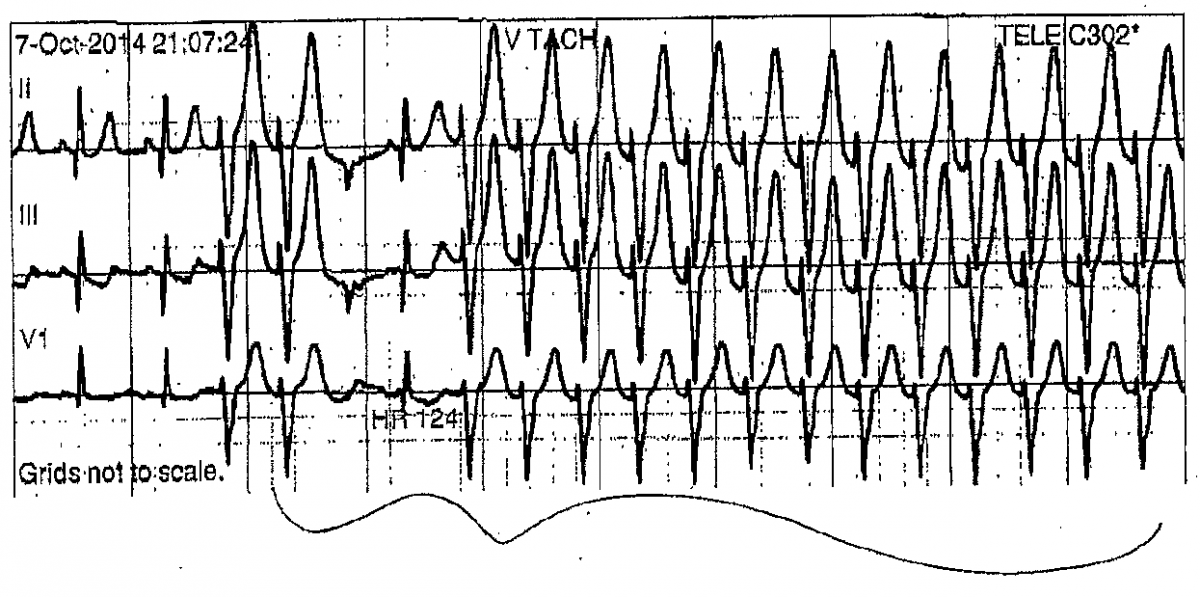

The following day, she reported having palpitations, and electrocardiographic (ECG) telemetry data showed 13 beats of ventricular tachycardia (Figure 1). Laboratory test results confirmed persistent hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia (Figure 2).

Figure 1. The patient’s ECG data showed ventricular tachycardia at the time of her reported palpitations.

Figure 2. The arrow indicates the point at which cardiac arrhythmia had occurred. Calcium levels remained low until the magnesium level was normalized, at approximately postoperative day 7, after which calcium levels began to increase.

Results of 12-lead ECG showed prolongation of the QT interval at 480 ms. She received prompt infusion of IV magnesium sulfate, followed by IV calcium gluconate. Over the following days, she required multiple infusions of calcium gluconate and magnesium sulfate to correct her hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia. Her paresthesia resolved by postoperative day 8, correlating with normalization of her serum calcium level.

Discussion. Our patient had hypomagnesemia, causing refractory hypocalcemia. Transient hypocalcemia is a common complication of parathyroidectomy that generally resolves by the fourth postoperative day. Occasionally, the sudden drop in parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels and subsequent influx of minerals into bone lead to a condition known as hungry bone syndrome (HBS), which is characterized by severe and persistent hypocalcemia with concurrent hypophosphatemia and hypomagnesemia. HBS has rarely been reported in the pediatric population, and documented symptoms have been benign, consisting of paresthesia and inducible signs of tetany.1-3 Our patient’s case is the first reported case of ventricular arrhythmia in a child secondary to HBS.

HBS was previously described in 2 adult patients who, after parathyroidectomy, had experienced worsening symptoms of hypocalcemia despite calcium supplementation. As in our patient’s case, only when the patients’ magnesium stores were repleted did their condition begin to show clinical improvement.4,5 This may be attributed to the important role of magnesium in calcium homeostasis, affecting both PTH secretion and peripheral resistance to PTH.6 Our patient’s case further demonstrates the importance of recognizing concurrent hypomagnesemia in this disease process and addressing this deficiency early in patients with it.

In addition, hypomagnesemia could have precipitated the ventricular tachyarrhythmia in this patient. Hypomagnesemia is known to shorten the cardiac action potential and lead to ventricular arrhythmia, including torsades de pointes. In postoperative parathyroidectomy patients, we recommend that magnesium levels be monitored, along with calcium levels, to avoid the occurrence of life-threatening arrhythmias.

It is exceedingly rare for the metabolic derangements following parathyroidectomy to lead to ventricular arrhythmia. We found 2 documented cases of this occurrence,7,8 both involving adult patients with chronic kidney failure who were on hemodialysis, placing them at increased risk for severe electrolyte abnormalities.

Our patient’s case is unique in that it highlights the risk of HBS, with potentially lethal outcomes, in an otherwise healthy child.

References:

- Kale N, Basaklar AC, Sonmez K, Uluoglu Ö, Demirsoy S. Hungry bone syndrome in a child following parathyroid surgery. J Pediatr Surg. 1992;27(12):1502-1503.

- Yeşilkaya E, Cinaz P, Bideci A, Çamurdan O, Demirel F, Demircan S. Hungry bone syndrome after parathyroidectomy caused by an ectopic parathyroid adenoma. J Bone Mineral Metabol. 2009;27(1):101-104.

- Simsek E, Arikan Y, Dallar Y, Akkus MA. Prolonged hungry bone syndrome in a 10-year-old child with parathyroid adenoma. Indian Pediatr. 2009;46(2):178-180.

- Jones CTA, Sellwood RA, Evanson JM. Symptomatic hypomagnesaemia after parathyroidectomy. Br Med J. 1973;3(5876):391-392.

- Desport JC, Bregeon Y, Devalois B, Karoutsos S, Sardin B, Lapraz J. Hypomagnesemia associated with hypocalcemia after undetected parathyroidectomy [in French]. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 1992;11(4):470-472.

- Fatemi S, Ryzen E, Flores J, Endres DB, Rude RK. Effect of experimental human magnesium depletion on parathyroid hormone secretion and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D metabolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1991;73(5):1067-1072.

- Gmehlin U, Marx T, Dirks B. Ventricular fibrillation due to hypocalcemia after parathyroidectomy with autotransplantation of parathyroid tissue in a dialysis patient. Nephron. 1995;70(1):110-111.

- Bacon NC, Mason PD. Ventricular tachycardia due to rapidly changing serum calcium levels following total parathyroidectomy. Nephron. 1996;74(1):236-237.