Peer Reviewed

Asymptomatic Rash With Unusual Hair Shaft Deformities: A Case of Scurvy

AUTHORS:

Russell Newkirk, MD1 • Padma Chitnavis, MD2 • Wen Chen, MD3 • Mary Maiberger, MD4

AFFILIATIONS:

1Naval Medical Center Portsmouth, Portsmouth, Virginia

2Carilion Clinic, Roanoke, Virginia

3Department of Pathology, Washington DC Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Washington, DC

4Department of Dermatology, Washington DC Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Washington, DC

CITATION:

Newkirk R, Chitnavis P, Chen W, Maiberger M. Asymptomatic rash with unusual hair shaft deformities: a case of scurvy. Consultant. 2021;61(6):e29-e31. doi:10.25270/con.2020.10.00018

Received August 5, 2020. Accepted October 6, 2020. Published online October 13, 2020.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

DISCLAIMER:

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, or the US Government.

CORRESPONDENCE:

Russell Newkirk, MD, Naval Medical Center Portsmouth, 620 John Paul Jones Cir, Portsmouth, VA 23708 (russell.e.newkirk.mil@mail.mil)

A 56-year-old man, whose case was being followed by a dermatology practice for management of basal cell carcinoma, presented to a dermatology clinic with a 4-month history of an asymptomatic rash on his bilateral thighs. He also reported occasional sores in his mouth but noted that he did not have oral lesions at time of presentation. On further questioning, the patient reported recent weight loss secondary to poor dietary habits in the setting of limited financial resources. Suspicion for a vitamin deficiency was elevated, given this additional history.

Physical examination. Follicular hyperkeratosis was present on the bilateral thighs with perifollicular, violaceous halos and deformity of hair shafts, with enhancement of these features on dermoscopy (Figures 1 and 2). The hair shaft deformities resembled the classic corkscrew and swan neck hairs consistent with ascorbic acid deficiency/scurvy. The patient was edentulous, and no gingival abnormalities were appreciated. No nail changes were observed. No other pertinent findings were observed on the full-body skin examination.

Figure 1. Follicular hyperkeratosis was present on the bilateral thighs with perifollicular, violaceous halos and deformity of hair shafts.

Figure 2. Corkscrew and swan neck hairs on the patient’s thigh.

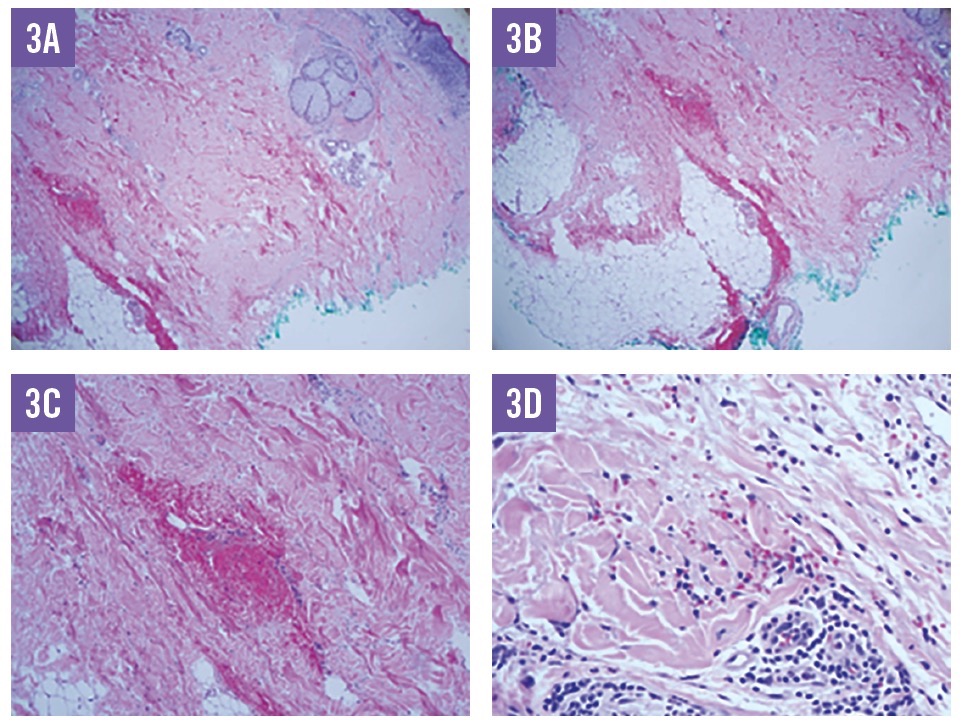

Diagnostic tests. The serum vitamin C level was found to be below the reference range at 0.1 mg/dL, and histology test results of a punch biopsy specimen revealed focal hemorrhaging in the mid to deep dermis (Figure 3), supporting the diagnosis of scurvy. Additional diagnostic testing included a complete blood cell count, the results of which were notable for a white blood cell count of 4800/µL, a hemoglobin level of 12.9 g/dL, and platelet count of 169 × 103/µL. Results of a comprehensive metabolic panel were notable for a serum creatinine level of 1.4 mg/dL but were otherwise within normal limits. Serum levels of zinc, biotin, vitamins B1, B2, B3, B5, B6, and α-, β-, and γ-tocopherols were within normal limits. Serum levels of vitamin A (35 µg/dL), folate (146 ng/mL), and vitamin C (0.1 mg/dL) were all below the respective reference ranges.

Figure 3. Histology results demonstrated focal areas of hemorrhage in the mid to deep dermis in close proximity to a pilosebaceous unit, supporting a diagnosis of scurvy, as well as some lymphocytic aggregates (A, ×40; B, ×40; C, ×100; and D, ×200).

Discussion. Scurvy is the deficiency of ascorbic acid or vitamin C, an essential nutrient that plays an important role in biochemical reactions, especially redox reactions, hormone synthesis, and hydroxylation of certain substances—most notably, collagen.1-3 Humans are unable to synthesize vitamin C and must obtain it from dietary sources, predominantly fruits and vegetables.2

Although the first historical records of scurvy date back to the ancient Egyptians, outbreaks of scurvy are most famously associated with European naval explorers and sailors who remained at sea for prolonged periods without fresh fruits or vegetables.1,2 The famous Portuguese navigator, Vasco da Gama, noted that several of his men became ill during his circumnavigation of Africa, with signs of swelling in the extremities and gums, but that their condition improved after eating oranges.1,2

Today, cases of scurvy are rare but do arise in situations in which there is a lack of knowledge about proper nutrition and in persons with psychiatric disorders, social isolation, and alcohol use disorder.2 Severely restrictive diets also have the potential to result in a nutrient imbalance that is capable of producing scurvy. Additionally, tobacco smokers have higher ascorbic acid catabolism and are thus more susceptible to developing scurvy.2

The characteristic skin findings of the abnormally coiled corkscrew hair shafts, perifollicular hemorrhage, and follicular hyperkeratosis were key to this patient’s diagnosis. Additional cutaneous manifestations of scurvy may include splinter hemorrhages of the nails and swollen, friable, hemorrhagic gingiva.2 While the diagnosis is usually clinical, laboratory tests and skin biopsy can be helpful in providing confirmation. Treatment of scurvy is dietary supplementation, with a recommended dose of 100 mg of oral vitamin C, 3 times a day.2 This dose is usually sufficient to correct the deficit and increase body stores.2 Resolution of symptoms, however, can occur with as low as 6.5 mg of ascorbic acid daily.2 Improvement in symptoms can be seen as early as 24 hours into treatment, with paling of the skin 2 to 4 weeks later, followed by a reduction in follicular hyperkeratosis and uncurling of the hair shafts.2 If treated, no permanent damage results, apart from lost teeth.2

In addition to the cutaneous manifestations highlighted in this patient’s case, other symptoms associated with scurvy include fatigue, lethargy, listlessness, depression, easy bleeding, xerosis, ecchymoses, bullae, and edema.2,3 Dyspnea, chest pain, syncope, shock, and even death may occur in severe cases.2 Ophthalmologic symptoms, anorexia, gastrointestinal tract bleeding, bone/joint pain, hemarthrosis, and osteoporosis are other possible complications but are difficult to assign solely to ascorbic acid deficiency, since other vitamin deficiencies typically occur concomitantly.2 Anemia and leukopenia are the most common laboratory test abnormalities associated with scurvy, although the platelet count and function are usually normal.2

Our patient was also found to have multiple other vitamin deficiencies upon laboratory evaluation. He received counseling on proper nutrition and was treated with oral vitamin supplementation. Mohs surgery of the previously diagnosed basal cell carcinoma was performed without issue and with good wound healing. At follow-up 4 weeks later, paling of the skin and a reduction in follicular hyperkeratosis and uncurling of the hair shaft was observed. Although the patient had other vitamin deficiencies, the finding of corkscrew hairs was pathognomonic of vitamin C deficiency. Additional vitamin deficiencies were found on laboratory evaluation, but no manifestations of these deficiencies were observed on physical examination.

This case represents a relatively uncommon disease process that can have serious implications if left untreated. Attention to detail of seemingly benign skin findings can be critical, especially in populations prone to nutritional deficiencies. Furthermore, increased awareness of nutritional deficiencies in general is warranted given the emergence of fad diets in popular culture.4 Certain diets may be effective in producing weight loss by severely restricting typical dietary components such as carbohydrates. This may set the stage for reduced vitamin intake as an unintentional consequence.

REFERENCES:

- Magiorkinis E, Beloukas A, Diamantis A. Scurvy: past, present and future. Eur J Intern Med. 2011;22(2):147-152. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2010.10.006

- Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Adult scurvy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(6):895-910. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70244-6

- Wijkmans RAA, Talsma K. Modern scurvy. J Surg Case Rep. 2016;2016(1):rjv168. doi:10.1093/jscr/rjv168

- Fomin DA, Handfield K. The ketogenic diet and dermatology: a primer on current literature. Cutis. 2020;105(1):40-43.